Limitations » Range Folding

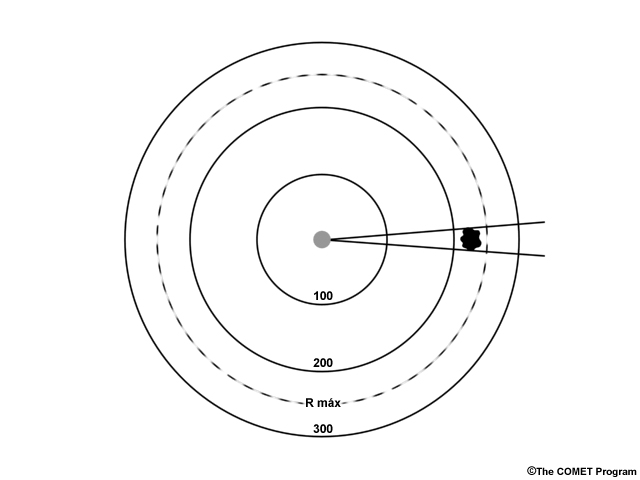

The time between pulses emitted by a radar must be long enough for any scattered energy from the first pulse to return before the radar has transmitted another pulse; otherwise, the radar will interpret the energy scatter from the original pulse as belonging to the second pulse. The maximum distance that a pulse can travel outward without this occurring is called the "maximum unambiguous range." For precipitation within the maximum unambiguous range, the radar pulses will go out and be scattered back to the radar before any additional pulses are emitted.

The location of the precipitation will then be plotted in the right location.

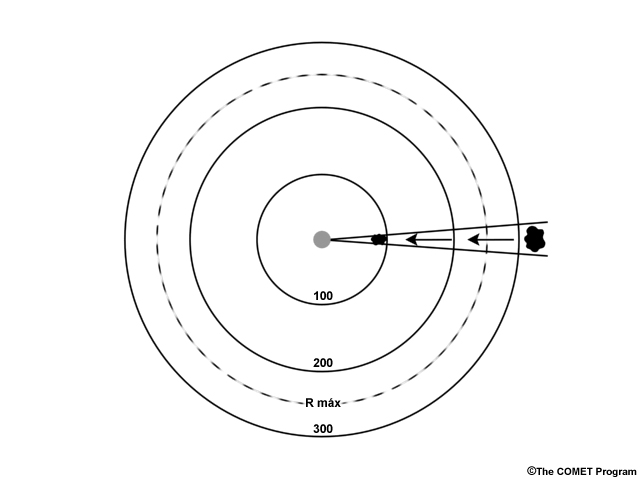

Now let's look at what happens when precipitation is located outside of the radar's maximum unambiguous range. After the pulse strikes the precipitation, the reflected portion is only able to make it part of the way back to the radar before a second pulse is transmitted. When pulse 1 finally does make it back to the radar, the radar interprets it as being a return from the second transmission, and it inaccurately places it closer to the radar. When they do appear, they often are elongated along the radial and may not look physically realistic.

On a plan view image, the precipitating area will appear narrower and closer to the radar than it actually is, and it may look physically unrealistic. These types of radar echoes are sometimes termed "second trip" or "ghost" returns. The NWS often uses scanning strategies that have brief changes in the PRF (pulse repetition frequency) to help mitigate this problem.